Personal details about Kyniska are hard to find in the record. Women now outnumbered men, and moved to fill a void of economic influence. Though Sparta technically won, its male population was drained by casualties. In 431, when Kyniska may have been nine, her royal father hurled Sparta into yet another war - the 30-year Peloponnesian War with Athens. She had two brothers, and was to be a rich heiress from birth.ĭuring her first years, Sparta was jarred by profound change. They saw Spartan women as “loose.”Īround 440 BC, Kyniska was born to King Archidamus II and his wife Eupolia. In short, everything Lakonians did was culture shock for other Greeks. Among the parthenoi, or young unmarried girls, lesbian passions found their voice in writings by the Spartan poet/educator Alcman. Older men and women might mentor young people of the same gender mentoring could include an intimate relationship. From early teenhood, boys lived in separate communes where sexual intimacy was common.

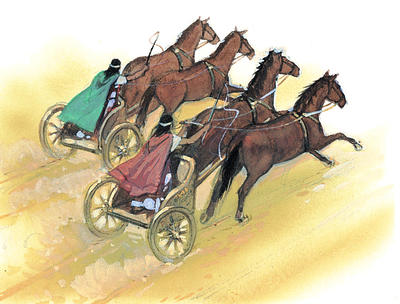

To ensure that every child had a good support system, Spartan women could inherit and own property, and they enjoyed more sexual freedom than other Greek women.Īlong with unconventional heterosexuality, the Spartans went a bit further than most Greeks on homosexuality as well - they institutionalized same-sex love, giving it a respectable place. Scantily clad or even naked, they went out for the same sports as boys. So Spartan girls got the same rugged public-school education as boys. To the Lakonians, a strong healthy active female was the ideal mother of soldiers, imbuing her sons with her own courage and toughness. 1 military power in Greece.īut Sparta achieved this by easing some of the heavy patriarchal strictures on women that were traditional with other Greeks. By channeling its citizens’ energies into a regimented, frugal, communal and clannish life, Sparta had clanked its bronze-armored way to being No. Though tiny, Sparta stood out among Greeks for its unconventional ways. The kingdom’s elite citizens numbered only perhaps 10,000 at its peak, supported by a larger population of freedmen and serfs (called helots). Outside its capital city, Sparta, were the fertile well-watered farmlands and a few mud-brick villages. One of the dozens of city-states that comprised Greece, it was no bigger than New Jersey - just a wide valley ringed by mountains and drained by a river, the Eurotas, that ran down to the Mediterranean. The ancient name for Kyniska’s homeland was Lakonia. The story of how Kyniska masterminded her way to glory through this loophole in the Olympics rules is one of the great game-changes in sports history – and it has a strong lesbian twist to boot. Painting of a tethrippon, or four-horse chariot race.

#Ancient greek olympics chariot races driver#

And the horse-owner was viewed as the winner, not the driver (who was usually a slave or hired professional). As owners, they could enter horses in the equestrian events… as long as a male charioteer was the public face on the entry. “But women couldn’t compete in the ancient Olympics, “ some will say.

In 396 BCE, Kyniska, a king’s daughter from Sparta, won it in the prestigious tethrippon or four-horse chariot race. The end of Women’s History Month is a good time for Outsports to celebrate the first female to wear a victor’s crown of olive leaves at the ancient Olympic Games. Kyniska's story is one of the great game-changes in sports history – and it has a strong lesbian twist to boot.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)